From 2012 to 2014, photographer Nana Varveropolou ran workshops in the education department of a detention centre in Middlesex. The project No Man’s Land is a result of her time there.

Could you describe your project, No Man’s Land?

No Man’s Land is a collaborative project that explores experiences of indefinite immigration detention at Colnbrook immigration removal centre, near Heathrow airport in England.

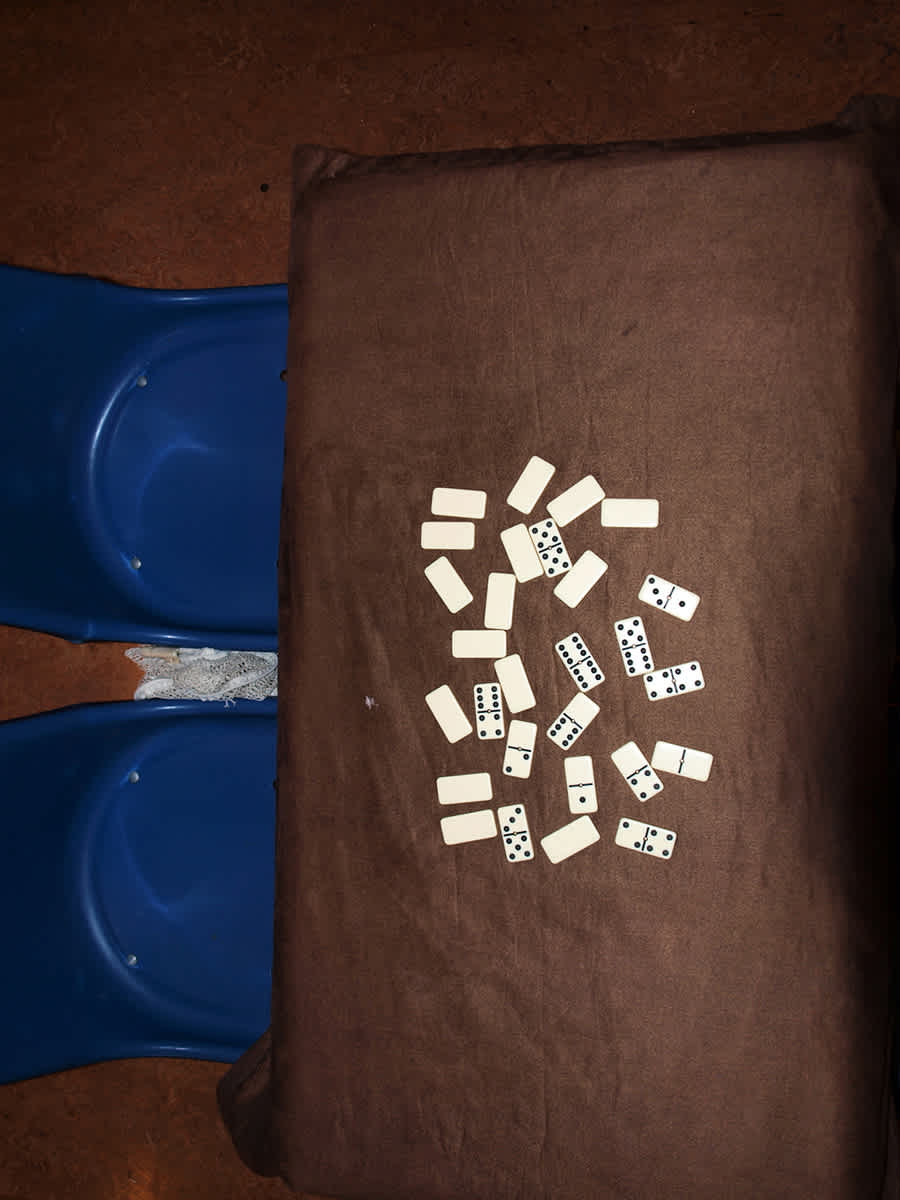

Over two years, a number of men detained in the centre participated in photography workshops that I devised and delivered – producing photographs around preagreed themes, such as time, powerlessness, patience and insomnia. Others explored their experiences through still life photographs of the few objects that they were allowed to keep in their ‘rooms’. While running the workshops, I was producing my own photographs of the spaces within the detention centre, as well as portraits of willing participants. Together, our activities created parallel records of detention, as seen from outside and inside.

Our collaboration aimed to explore the experience of long term and indefinite immigration detention, particularly the effect it has on those who are stuck in its centres. The workshops used were developed in response to conversations and interactions between myself and the participants over a long period of time.

How were your workshops structured?

The process of making the project was completely organic. To be completely honest, before I began the project, I hadn’t thought of it being collaborative. I agreed to run the photography workshops as a means to gain access to the centre, but they became part of the project. Almost immediately I realised that it was only through dialogue and collaboration with participants that I would be able to understand the issues, and that it was only them who could really tell the story.

Once I accepted and adjusted to this new way of working – after all, this project wasn’t just mine – things started to make sense. The first big shock was the loss of control. Having worked a photographer for a number of years, I was used to having authority when it came to ideas, processes and outcomes. In our collaborative work for No Man’s Land, that control entirely disappeared and I did find it quite difficult to start with. I would visit the centre once a week, but it took about a year to properly develop the collaborative strategies that have since shaped and defined the project.

How did you come to work at Colnbrook?

I was looking for a way to gain access to detention centres in the UK, and the organisers of the brilliant initiative Refugee Week told me about a project called Music in Detention, which was delivering music workshops at Colnbrook IRC. They kindly put me in touch with the head of the education department at Colnbrook. To my surprise, the department responded rather enthusiastically to my email – they were trying to expand their education activities and were keen to include photography workshops. Though I was fortuitous in contacting the right person at the right time, it’s also true that the private companies running detention centres for profit receive an extraordinary amount of money to do so. When they are over budget (which they often are), they spend money on education so that their surplus funding isn’t cut. I met with education staff a couple of days after my initial email and agreed that I would deliver the workshops free of charge in exchange for permission to photograph the centre and any detainees willing to be subjects. The centre agreed, with only three conditions: 1. Never mention the private company that was running Colnbrook at the time. 2. Never photograph door locks. 3. Never photograph staff.

Over two years of visiting the centre weekly, I believe I became somewhat ‘invisible’ – relationships of trust were built not only with the detainees that I was working with, but also with the centre staff and guards. After a while, I was more or less free to take photographs anywhere I wanted (accompanied by a designated guard), and we could develop the photography collaboration in whatever direction we chose, without any interference from the centre. My bags were never checked and neither were the materials that we were producing. I still find this surprising when I think about it.

How did the project shape your own understanding of detention?

I started the project with very strong feelings about indefinite immigration detention in the UK, but it was only after a period of extended and ongoing conversations with the participants that I fully understood the breadth and depth of the issue. It is these conversations that are at the heart of this project – they led us to the themes we used as context for photographs.

Indefinite detention is cruel: it traumatises anyone caught in its system, and it often punishes the most vulnerable people simply because they have made an asylum claim. The UK is the only country in the EU that doesn’t put an upper time limit on detention. Colnbrook IRC is built to Category B prison standards, and it operates under a prison-like regime.

How did you acknowledge the increasing periods of time that people are spending in detention centres?

The men I was collaborating with for this project were mostly there for long periods of time. Seven months was the shortest period that I encountered and six years (!) was the longest. People subjected to detention are often stateless: not accepted by their countries of origin, but not allowed to stay in the UK. Being in detention for a long period of time, without a date for deportation or release (unlike prison inmates) has a tremendous impact on detainees’ mental health. Many men I met were suicidal and most were depressed – these issues became our primary exploration throughout the project.

Have you witnessed many changes in the detention system since beginning No Man’s Land?

There are some brilliant organisations (Detention Action and Refugee Council, among others) that have been fighting long battles against indefinite immigration detention in the UK. There have been victories, achieved through hard work. For example, in 2015, Detention Action successfully halted the UK’s ‘detained fast track’ system, which detained rejected asylum seekers and gave them a strict seven day period to appeal their imminent deportation. But the central issue remains: people are still detained without any time limit in the UK, and increasingly they are trapped in these centres for years on end. Sadly the current political climate – in the UK and beyond – does not look promising for improvements to immigration and asylum policy. Things seem to be getting worse rather than better.