A Liberian displaced person who lived in 2002-03 (at the height of the civil war between Charles Taylor and the LURD rebels) in a camp for the internally displaced, on the outskirts of Monrovia, became a refugee in 2003 if he then fled to a UNHCR camp in the forest region of Guinea and was given the qualification, then an illegal if he left in 2005 to seek work in Conakry, where he would come across many compatriots living in the Liberian quarter of the Guinean capital. Then, after spending days at the bottom of a cargo boat, he might try to enter Europe, ending up in one of the hundred or so ZAPIs (waiting zones for persons under review) at the French ports and airports. He will now be officially considered a detainee, before he can be registered as an asylum applicant, with a 90 percent chance of being rejected, his demand being classified by the OFPRA agent as ‘manifestly unfounded’. He will then be taken to the frontier and expelled from France, or else held in a CRA 1 while waiting for the administrative procedure necessary for his expulsion to be finalised (which may take weeks or months), or again left at liberty in the situation of a non-expellable irregular. He then becomes a sans-papier, a status somewhat close to that of tolerated, which is given in Poland to a person in a situation similar to his own – generally, in that case, to Chechens. If he makes a further request for asylum, he runs a heavy risk of being rejected again, as Liberia is no longer considered a dangerous country since the peace agreement of 2004 and the surrender of Taylor. 2

As we read through this anecdote of a hypothetical displaced person, it is clear to see that the architecture and legal protocols that form the infrastructure of humanitarian governance are intertwined. They are spread across national and international borders, a multitude of typologies, a variety of legal frameworks, temporalities, and most importantly, through this infrastructure, an array of naming practices are formed and attributed to persons in flight.

Due to conflict, climate change or other forms of upheaval, people become displaced and in turn forced to migrate. This forced migration intersects a person with various forms of infrastructure – such as camps, borders, detention centres, registration centres, deportation waiting zones – and through each, a displaced person becomes a detainee, deportee, illegal immigrant, asylum applicant, among many other things.

These encounters between architecture and law through humanitarian infrastructure expose people fleeing conflict to new forms of discrimination, be they institutional or otherwise – wherein architecture becomes both actor within, and register of a contested political and social force field.

The operations that permeate humanitarian infrastructure are not only administrative but also inherently extractive. The names and identities that anthropologist Michel Agier points to in this conjecture are the result of extractive processes of a financial and biopolitical nature. Conducted through operations – by both state and inter-state organisations, such as Frontex, as well as non-state entities such as corporations and criminal enterprises – that draw out a form of value from the body of the displaced through biometric and logistical processes, converting the person and their body into a resource for financial or biopolitical gain.

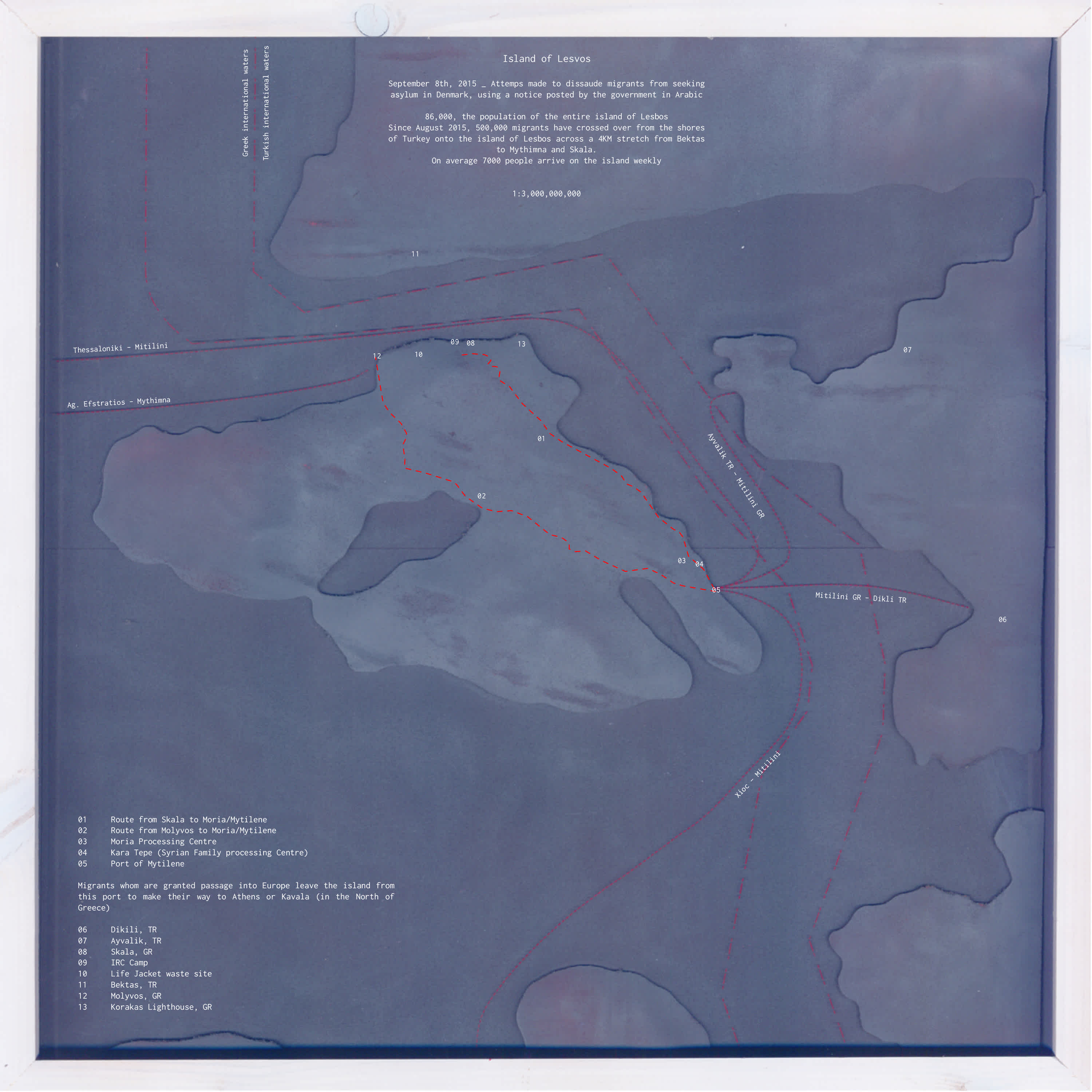

We can observe these dynamics through the crisis that has unfolded as a result of the civil war in Syria. Having entered its sixth year in March 2016, with 12.2 million people situated within the confines of the country in need of life saving aid, 7.6 million internally displaced, more than 212,000 people trapped in besieged areas without access to humanitarian assistance and over four million people fleeing across borders. 3 In the same month, the European Union came to an agreement with the government of Turkey outlining procedures that would stem smuggling operations across the Aegean sea. The EU-Turkey deal states that irregular migrants who have arrived on Greek islands from Turkish shores will be deported back to Turkey, in exchange for the relocation to EU member states of Syrian asylum applicants who have indeed followed legal protocols.

The conflict in Syria has a direct impact on the Greek island of Lesvos, a key point on the migrant route to Europe. In 2015, over 416,000 Syrians arrived on the Greek island. 4 In February 2016 alone, 30,000 asylum seekers from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan made their way to Lesvos. 5 It is within this island that we see a large concentration of both architectural and institutional infrastructure, each with their own form of financial and/or biopolitical calculus – ranging from those that have come to exist as a direct consequence of the influx on the island (small local NGOs and local residents scavenging wrecked boats to mention a few) to institutions and corporations (such as UNHCR and telecommunications company Vodafone).

Naming practices, the politics enforced through them, the extractions that they enable and the precarious situations that they place lives in, are and have been present and ingrained in contemporary humanitarian governance. For this reason, the events that took place on and around the island of Lesvos in the spring of 2016 are key to understanding the greater apparatus that legally, spatially and temporally produces the differential identities attributed to the bodies of displaced populations.

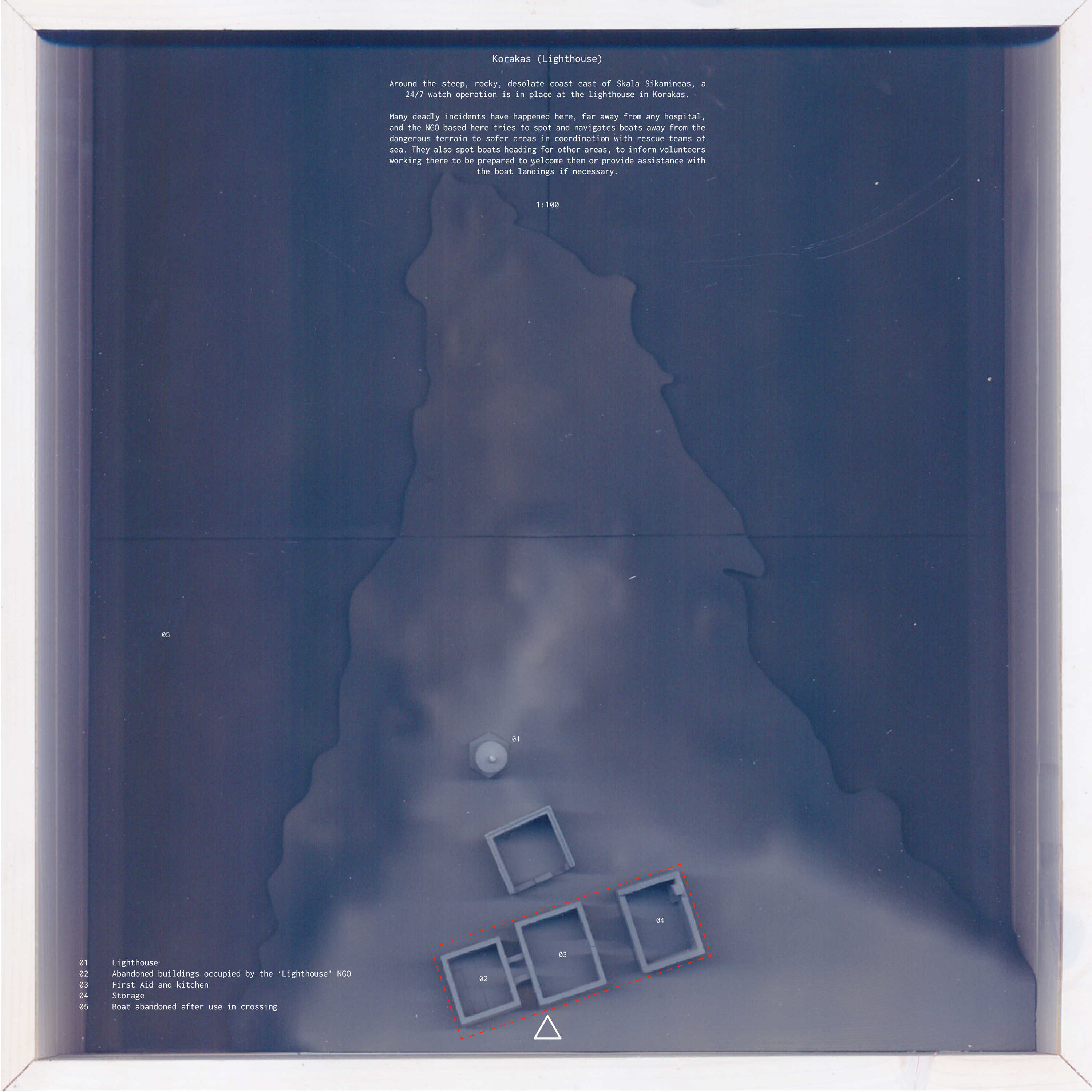

Korakas

Korakas is located ten kilometres away from the shores of western Turkey on the Aegean sea, a small rocky point on the north east of Lesvos. There, a lighthouse stands, built to deter boats and ships away from the perilous terrain it sits on. However, at Korakas, it acts as a beacon for those who have decided to cross the sea to reach the closest frontier of Europe – either independently or with the aid of smugglers.

Adjacent to the lighthouse, there stands three almost identical derelict buildings (presumably the residence of the former lighthouse keeper), which have now been occupied by the Lighthouse Relief NGO (named after the space they occupy). Each building accommodates a different requirement: storage of provisions and medical equipment, an area for medical assistance, and a lounge which doubles up as sleeping quarters. The volunteers – formed of lifeguards from various European countries – take turns day and night to observe any movement on the waters. Once a vessel is spotted, the team reacts instantly to make sure that everyone is accounted for safely and swiftly. The lifeguards take their own rescue boats into the sea to guide incoming vessels toward the rocky shores where they disembark. Once on dry land, each passenger is given immediate medical attention.

The remnants of destroyed boats, clothing and life jackets scattered on the rocky terrain are testament to the tragic events that have occurred there. In the island’s regions where such arrivals are common, the local economy has adapted: ‘scavengers’ roam the shores to find boat parts and motors to supplement their monthly income.

Here the most obvious tension lies between the humanitarian aid workers and the government of Greece. NGOs operating at the island’s camps and arrival points record details of each individual in order to offer aid and medical care. Because of the direct relationship between NGOs and the displaced, the acquisition of information from each individual is seen as far less intrusive compared to interactions with police or military bodies. However, under pressure from both the EU and internal turmoil, the state extracts data from these NGOs. The information is repurposed to identify and record each individual with quantifiable characteristics, which in turn grant or refuse asylum.

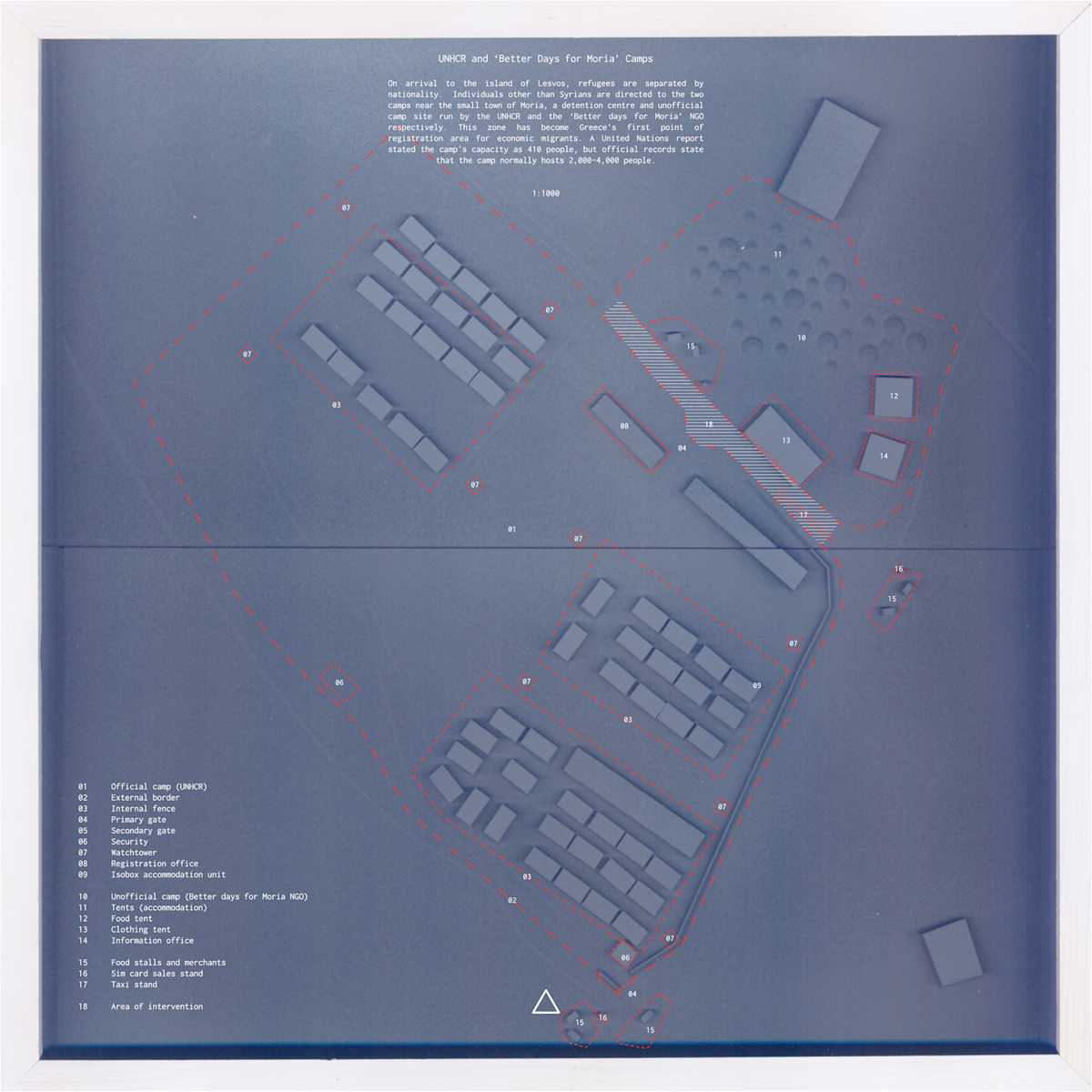

Moria

Individuals that arrive on the island are likely to find their way to one of its refugee campsites. The most prominent being the Moria refugee camp located five kilometres north of the capital of the island, Mytilini. The site is home to two very distinct camps, divided by a road. A UNHCR camp – heavily fortified, with barbed wire fences, armed forces, watchtowers and a four-metre-high concrete retaining wall – comparable to a prison in its set up. On the other side of the road, an informal ‘refugee’ camp formed in response to the fortification of the UN camp opposite. Managed by the Better Days for Moria NGO, the camp has flexible and ad hoc planning. The difference in life and vibrancy between the two is evident.

The only piece of infrastructure on this site linking the two camps is the registration building situated between the two – to which everyone must visit, registering their arrival and to make a formal application to leave the island and carry on through Europe to their desired destinations. Registration requires each person to present identification (ideally in the form of a passport), in doing so their country of origin can be taken into consideration. This procedure holds great value: people that are not from countries deemed in conflict (namely Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan in the years 2015 and 2016) were immediately refused passage from the island to mainland Greece. The registration centre, in this case, is that which performs the extractions that categorise new arrivals firstly by their country of origin, then by their gender, followed by their marital/family status. The first act of categorisation undertaken on the campsite.

Although it is an individuals’ choice as to which camp they choose to reside in, each option has its trade offs. Perhaps most notably, the informal camp does not have provisions for hot water or heating, which can be problematic in the island’s harsh winter climate, but it is well known that the UNHCR camp is governed like a detention centre, with limited accessibility and freedom.

Along with the contrast between the two institutions in this location, we can observe multiple layers of economic extractions at play. A Vodafone stand sells SIM cards to displaced people at the exit to each camp, with half price boat tickets to Athens bundled in as a promotional deal. Nearby food trailers cater for volunteers, journalists and the residents of the camps, charging more than the average value of products sold on the islands. Taxi drivers form queues to transport people to the harbour for extortionate prices. These transactions are (in principle) economic, which serve only to profit from the presence of the displaced.

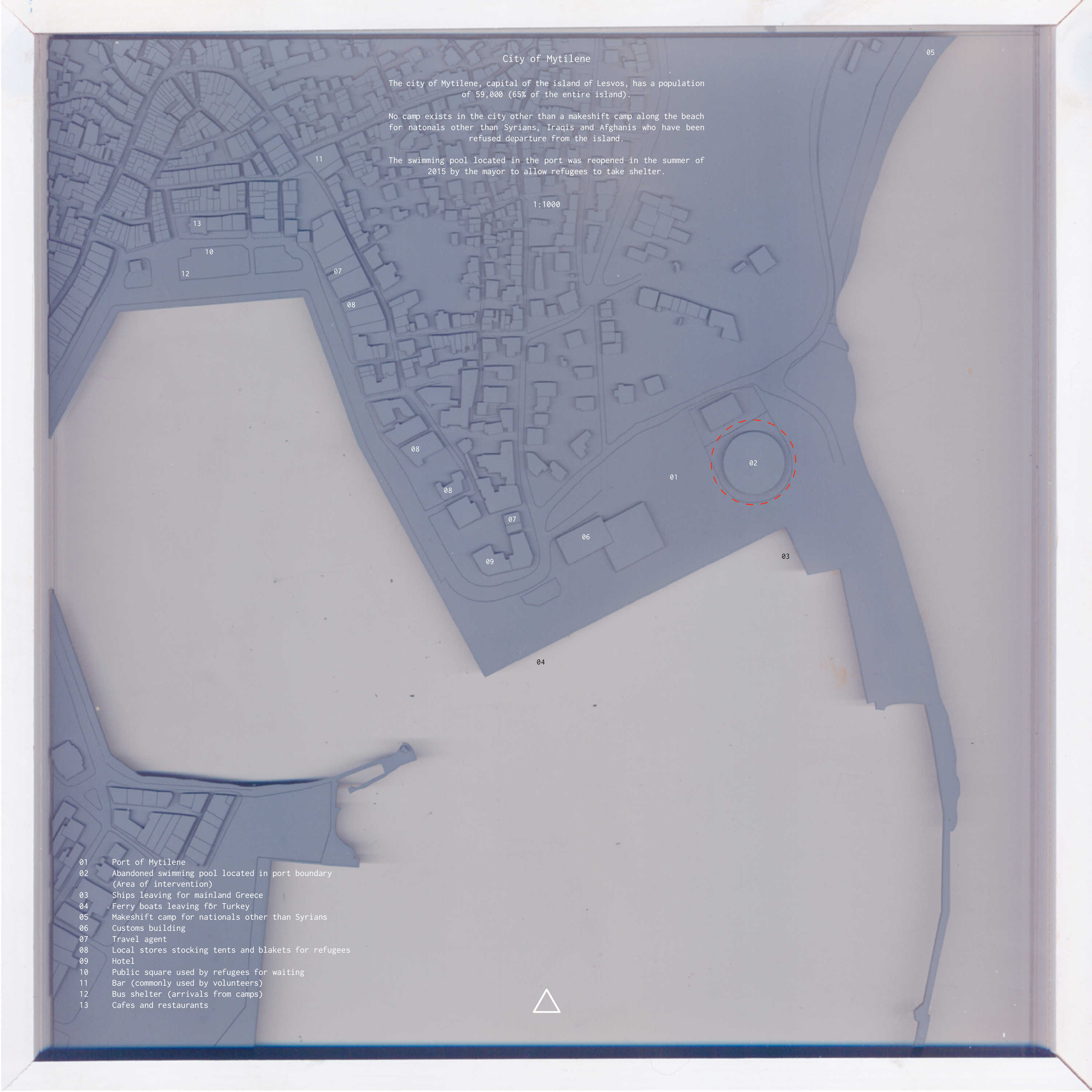

Mytilini

The city of Mytilini is the main departure point from Lesvos to the rest of Greece. As the island’s capital, it is home to nearly 50% of its population – around 30,000 people in 2016, excluding the displaced. 6 In the summer of 2015, with autumn and winter approaching faster than any long-term solution, the city’s mayor reopened an abandoned indoor swimming pool located in the harbour as shelter for passing individuals. Approximately 2,800 square metres in area, the building is derelict and completely unmanaged. Elsewhere in the harbour, local travel agents operate with placards and posters translated into the Arabic language, catering for the new travel market formed by the presence of the displaced.

Without official approval from the registration centre located in Moria, transient individuals who have arrived on the island have no legal means of departing. They are confined to a prolonged intermittence.

***

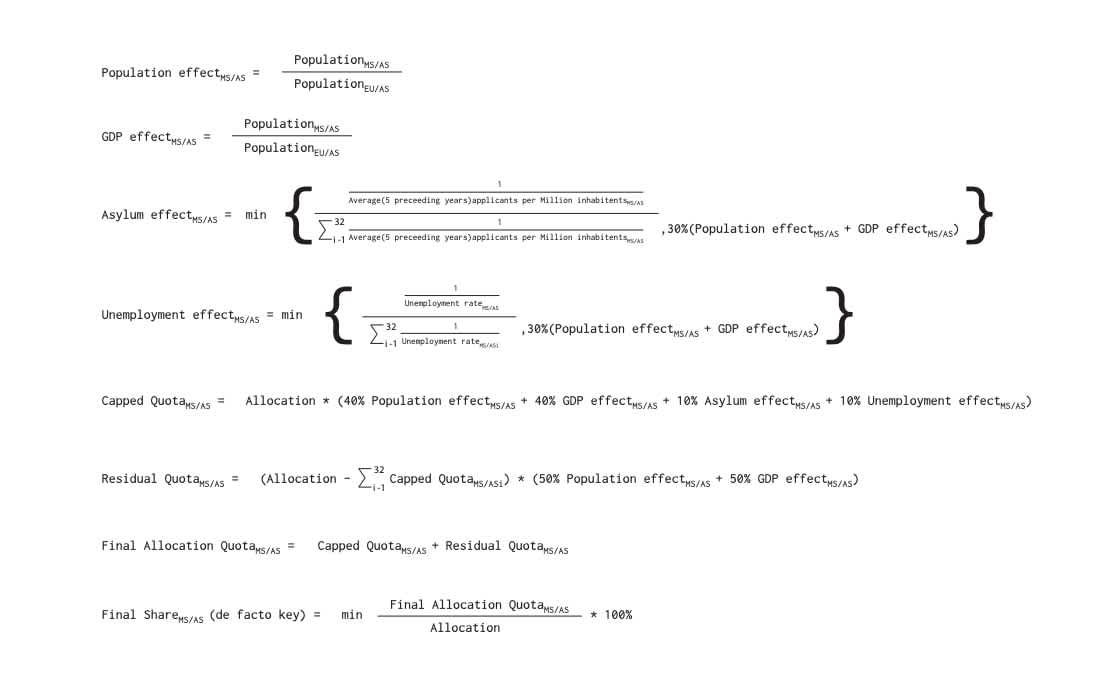

In September 2015, the European parliament formulated an algorithm for calculating the distribution quota of the displaced to each member state. 7 This algorithm produces what it calls a ‘fair share’ among member states, through multiple equations that take into account their population, GDP and unemployment rates.

Considering a person as a unit that is to be placed into an algorithm dehumanises every individual constituent. Similar processes occur in national news outlets worldwide, where displaced populations are presented in large figures. These procedures aim to homogenise large numbers of people and render their individual characteristics redundant. And in doing so, such algorithms are allowed to function without regard for any human value.

What is important to understand from these sites – Korakas, Moria and Mytilini – and the extractive processes undertaken on them is that they aid in the production of specific subjectivities, which put into question our understanding and definition of a ‘refugee’.

The 1951 Geneva Convention defines a refugee as follows:

A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.8

However, this is a definition that has been – and remains – open to interpretation by various governments and institutions. Differing interpretations have made humanitarian governance increasingly complex. Certain EU member states have proved it acceptable to cite suitable interpretations as excuses for xenophobic acts of denial and nonassistance. In the summer of 2015, having ordered the construction of a four-metre high wall along its 175 km border with Serbia,9 the government of Hungary argued that the ‘inevitable culture clash between Muslim migrants and their host country’ risks the harmony of the latter.10 This highlights clearly the malleability of the term either in favour, or indeed against the displaced.

A person in flight becomes abstracted through seemingly precise economic and legal categories, yet our general understanding and definition of the ‘refugee’ remains hazy. These factors work together to produce the varying spatial organisations across the three sites of Korakas, Moria and Mytilini – a situation that cannot be conveyed in numbers and calculations. This concentrated mechanism on the island of Lesvos is exemplary of the greater apparatus operating throughout Greece, its neighbouring countries and Europe. Ultimately aiming to manage and police individual lives in need of aid, placing human rights in a systematic process of approval and denial – with the statistical probability of denial standing at a 90% average across Europe as the management of the asylum application process has become increasingly privatised: companies that fail to meet denial quotas set by each country risk nonrenewal or termination of their contracts, rendering this process both systematic and financial.11

Therefore, we can argue that the identities produced and enforced onto the displaced are the direct result of this collaboration between law and architecture, wherein the material realities of this infrastructure does not only include architecture but also the piece of paper onto which law is inscribed, and the semiotic nature of law is not only reserved for policies and protocols but also the EU algorithm for allocating the displaced among its member states. Understanding the processes by which a displaced person is attributed identities as a result of specific assemblages, allows us to tease out the complexities and nuances of border regimes, their financial and biopolitical nature, and the subsequent extractive practices that they entail.

Having considered the island of Lesvos and the processes that are deemed humanitarian that take place on, around and through it, we must now ask: Is there a possibility for the reinvention of humanitarian aid, government and non-government institutions and their operations, within which the refugee can be more than an object of financial and biopolitical calculus?