The first time I went to the Balkans in July 2015 hardly anyone in Western Europe or the US was talking about a ‘refugee crisis’. When I visited again later that summer, the crisis had become global news.

When I landed in July I immediately began photographing the huge numbers of people arriving daily into Gevgelija, the Macedonian town on the border with Greece. Since there was almost no coverage of what was going on, I thought it was important to show the conditions that people were forced to travel in, and the dangers they were facing to escape from war and persecution.

Once I was back home in London my work seemed superficial: the photographs illustrated the situation, but they didn’t say much about why these events were happening. They couldn’t explain the absurdity of the system.

When I went back to the Balkans in August, my mind was filled with the images of the ‘refugee crisis’ that had been circulating in the news back home. I felt like I needed to find a more personal angle to the story. I wanted to go under the surface of what we were seeing in the news.

I stayed in Gevgelija again and although I was also covering the news, I took some time to observe and think about the situation. After about a week, I felt frustrated and incapable of explaining what I was witnessing in pictures.

I went out to the countryside, teetering on the border between Macedonia and Greece. I traced a path through the fields: all refugees who are allowed to enter Macedonia have to pass down this track.

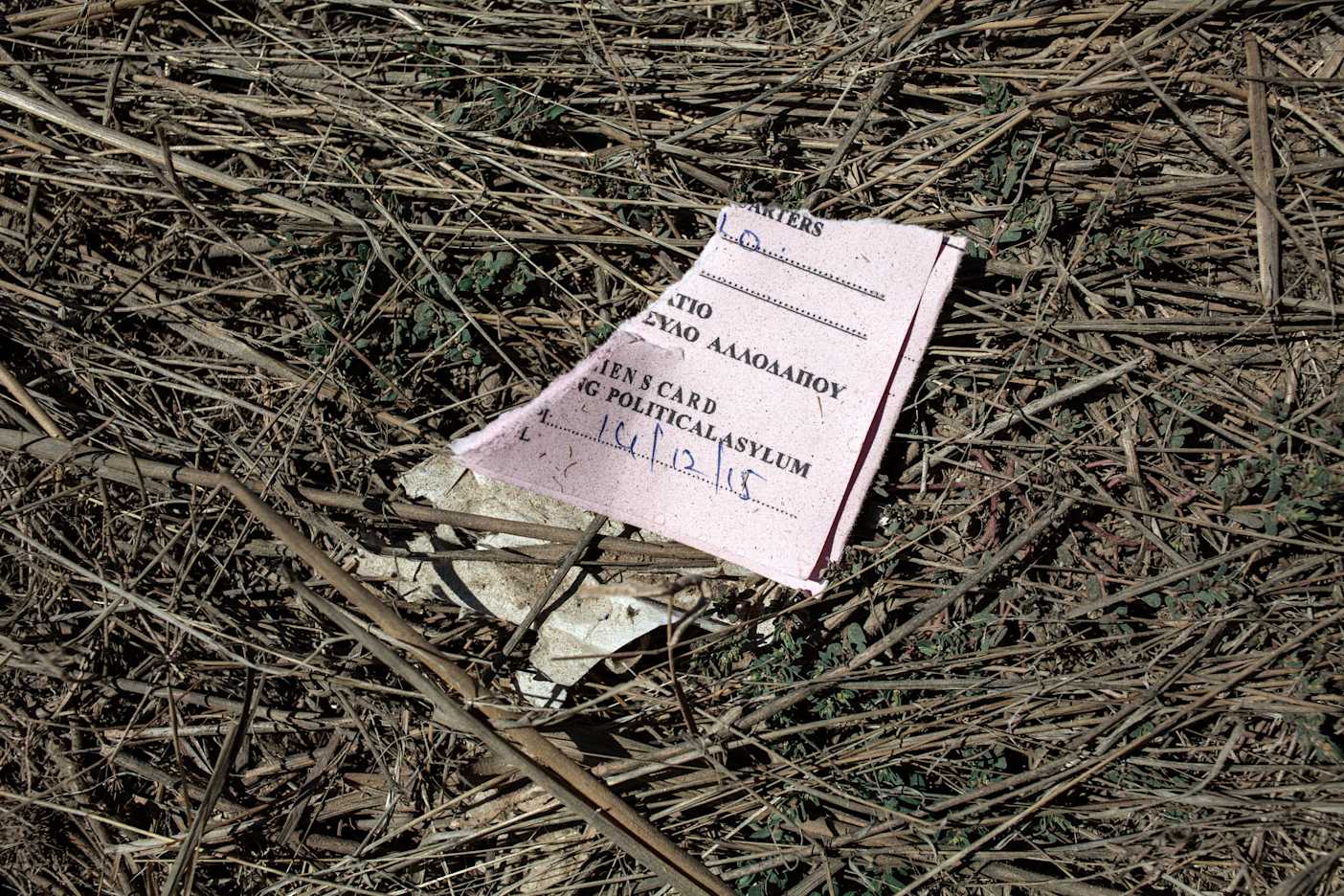

Walking down the path, I saw soft, pink, torn up pieces of paper scattered ahead.

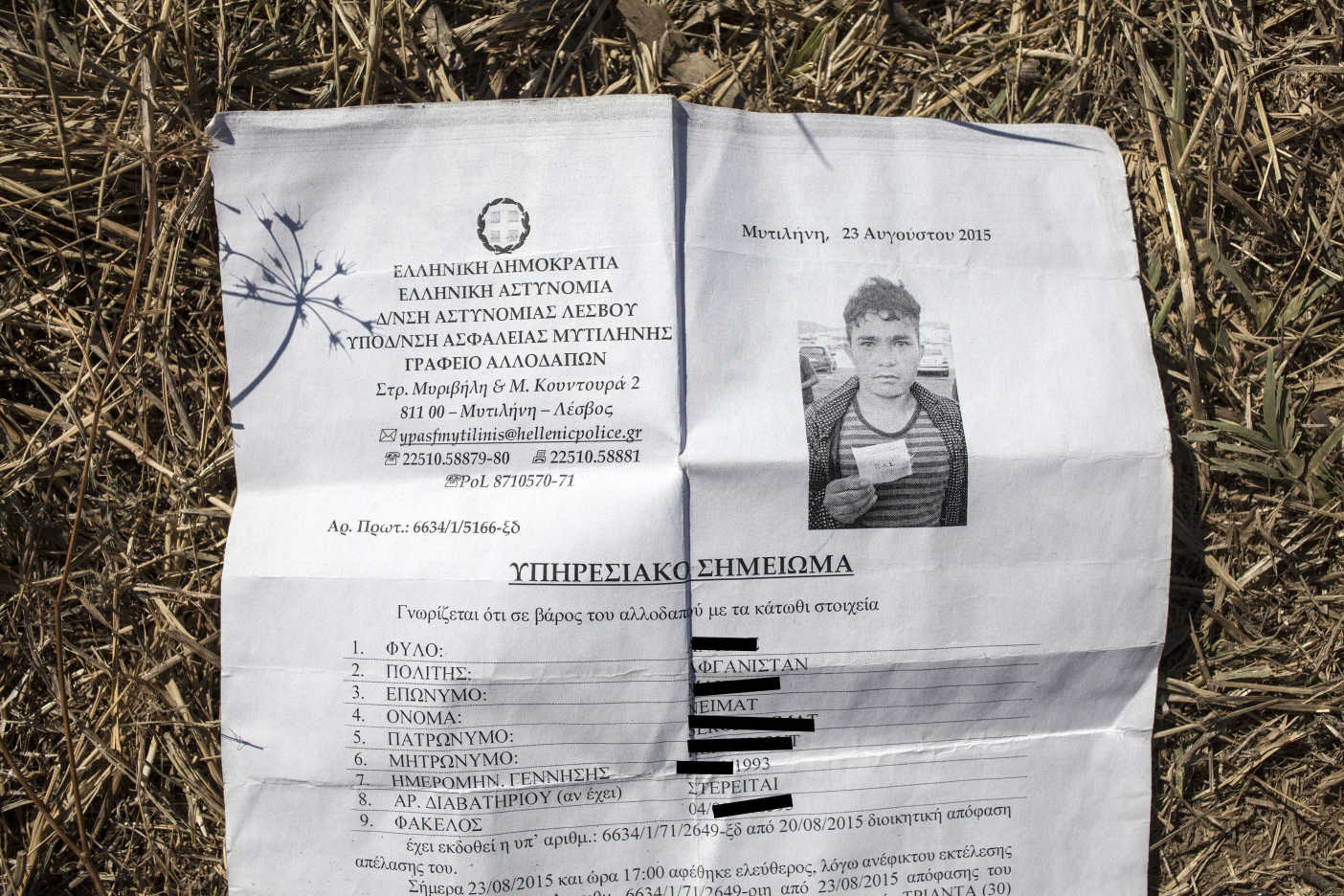

On closer inspection, I saw they were temporary IDs discarded by refugees after crossing the border into Macedonia. The documents are only valid in the country that issued them: within just a few metres, they had become useless scraps of paper.

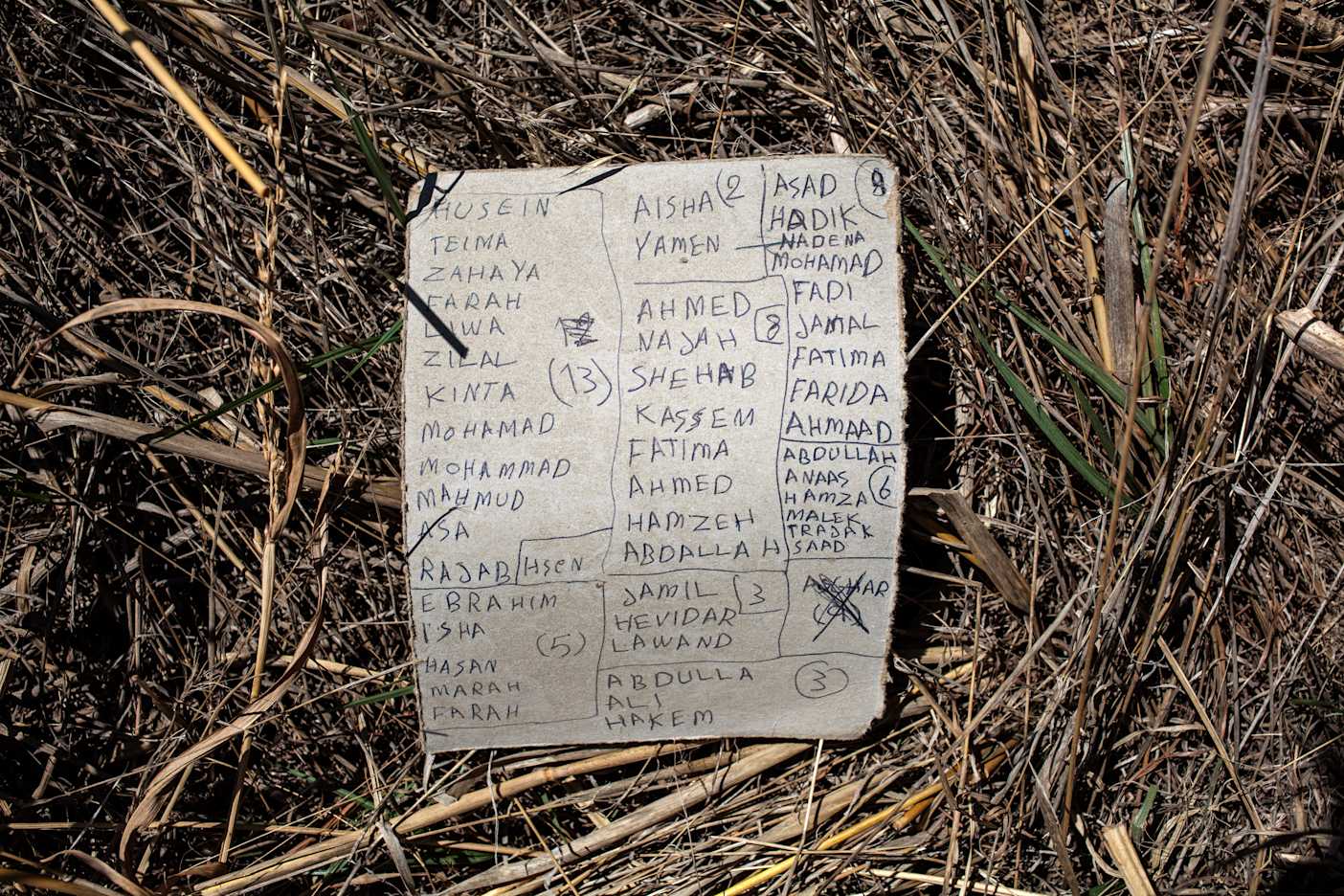

As I walked along the path, I found more useless scraps of paper: asylum request forms, maps, and lists of names.

I decided to start photographing these documents exactly as I’d found them – recording the traces that people were leaving behind, more like an archaeologist than a journalist. I spent two days walking back and forth on the stretch of land between the border and the temporary camp, photographing all the ‘papers’ I could find.

Police officers and officials refer to any kind of document as ‘papers’ in the camps and along the route to Europe. Your ‘papers’ are precious: the difference between moving freely and being held in a camp without knowing when or how you might be able to move on.

But that’s all they are: just papers. So many people are denied a safe passage to Europe based on their passport: just papers. They are a testament to how people’s lives are affected by bureaucracy.

ID cards are supposed to represent and validate an individual’s existence – to see them torn up and thrown away felt like bearing witness to a loss of identity. But your documents don’t determine who you are, rather where you can go.