I

*This is a transcript of a conversation which took place between the actor (S) and interpreter (N) before the filming of And if the asylum seeker does not wish to participate in the interview? in June 2016, Athens.

N: When he has relaxed – [reads from the sheet of questions in front of him] ’Your papers, please. Where are you from?’ [interrupts the reading and comments] You already have some documents, the file of the person in front of you, but to confirm his details you need to ask him too.

S: Because they might be fake?

N: To see if the last time he told the truth or if he lied. Ah, we need to add this at the end – ‘Is the information you gave us true?’ – before ‘Your papers please’. [Continues in a reading voice] ‘What languages do you speak?”... “Which languages do you speak?”... so we can find the right interpreter... “What is your native language?”?

S: Isn’t ‘What is your native language?’ enough?

N: ‘What is your native language?’ also. We should ask this as well, but we might not have an interpreter in your native language, so it is good to ask what other languages do you speak so if I don’t find one in your native language I can find one in another you speak well.

S: Oh, ok. Maybe – ‘What other languages do you speak?’.

N: Yes. Let’s change it – ‘What is your native language?’, ‘Which other languages do you speak?’

[sound of the printer]

S: So people in the interview committee are friendly?

N: The committee is friendly. The secondary committee is friendly, these committees are not under the police department.

S: They are not interrogators essentially?

N: The previous interviews, the first interview which happens at Petrou Ralli, is under the police department, so the policemen are not very familiar with these things -–their role is different, they are under pressure...

S: Who is under pressure?

N: The asylum seeker. [reads aloud] ‘Can you describe the problems you faced with the authorities in your country of origin?’

N: Better to say – ‘Can you describe the problems you face with the authorities in detail?’

S: ‘In detail’ or ‘with details’? Is ‘in detail’ a bit excessive?

N: They are going to ask you in detail. Because this is the second interview, so you have come across this question before.

S: Oh, ok.

N: During the first interview which is summative – based on this you will receive a document that expires in 6 months – at least that’s how it is here in Greece. And then after this, when your card expires, you will go to give an interview with details.

[typing sounds throughout]

S: So, ‘could you describe the problems you faced with the authorities in your country of origin in detail?’.

***

N: ‘Good morning’ – make a small pause after this. And don’t forget to use ‘sas’ [the formal version of you]

[sound of cicadas throughout]

N: Why use ‘route’ and not ‘journey’?

S: Maybe ‘route’ because there are specific ways of coming to Europe, from Turkey or from Cyprus for example.

N: ‘Journey’ is the right one to use. So here I have added ‘journey’ instead of ‘route’. ‘Route’ sounds like it has to do with cars or movement of goods or an established path. ‘Journey’ is similar, but it relates to a ‘journey’ by foot more, or the whole of their travel. [Reads] ‘Did you pay someone?’ ‘Have you applied for asylum in any other country? Why did you flee your country? Why did you not settle in the country you lived previously?’ – Here you make a pause and say – ‘For example, Turkey or Iran or any other country you crossed?’

[Reads] ‘Are you a member of an organisation or party in your country of origin?’– So we know what the reason is as to why they are fleeing their country. ‘Are you seeking political asylum? Did you flee due to political beliefs? Was it because of religious reasons?’

II

The scene

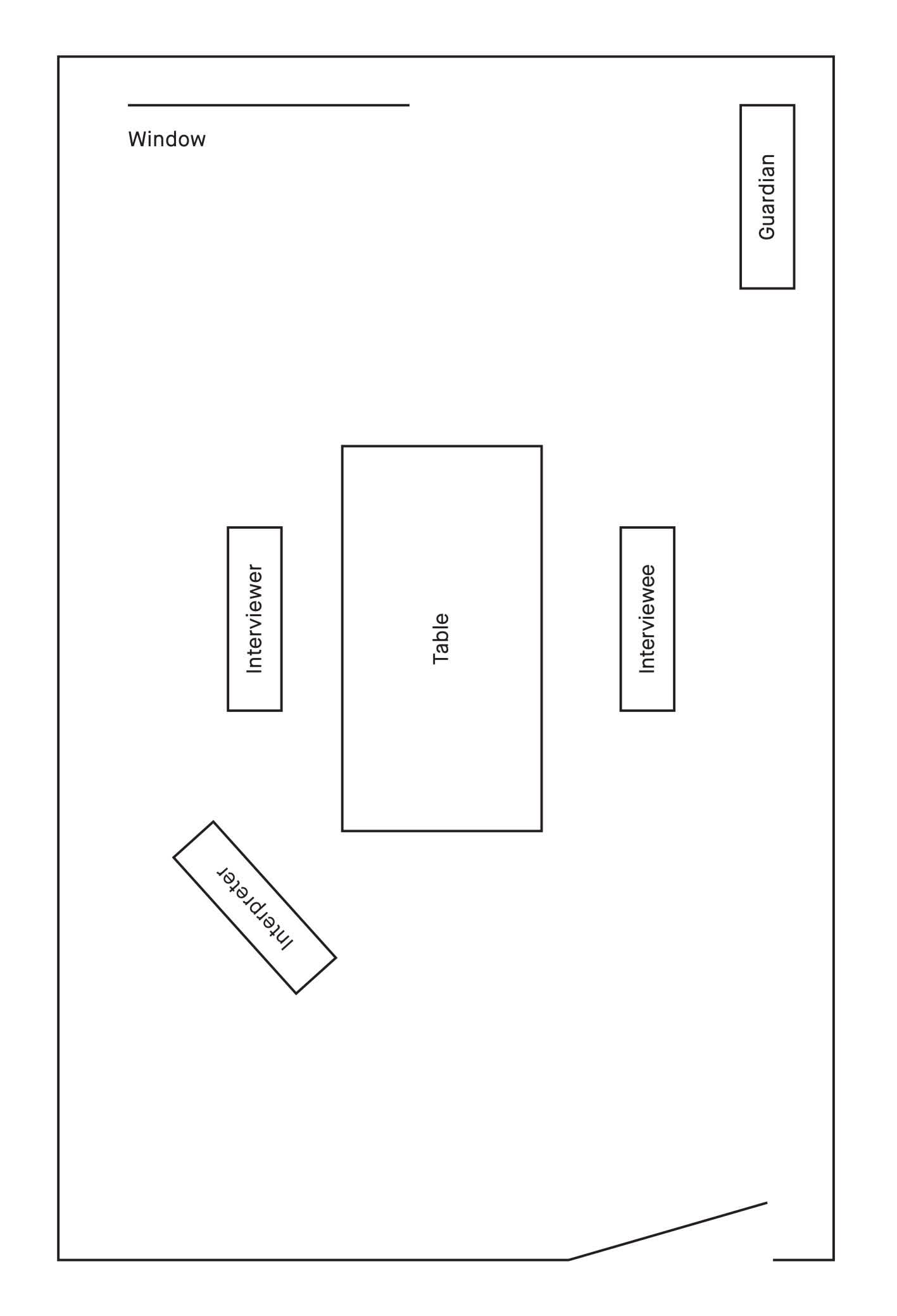

The physical place is very crucial to the interview. It is possible that there is not a chance of choosing the space for the interview: it is essential that attention is given to the details, as they influence the general atmosphere.

Every attempt possible should be exhausted so the environment is comfortable and the impression of respect as well as the impression that all attention needed would be given to the interviewee should be communicated through the interpreter. Additionally, the case officer should check, for example, whether any recording or other equipment, if required, is working. It is considered to be good practice for the case officer to provide a drink of water and have available tissues during the course of the interview, should they be required.

The desk and the chairs must be on the same level and if possible in a light part of the space.

It is essential to avoid symbols indicative of power within the interview space and the surrounding space (ie. arrangement of the space reminiscent of a courtroom, metal bars on the windows, locked doors, presence of staff in a uniform etc.). In addition, it must be avoided to give a seat to the asylum seeker where he or she is ‘blinded’ by light.

The arrangement should be so that the interpreter is at the side of the interviewer, in a position that does not obstruct the view between the asylum seeker and the interviewer.

If the asylum seeker is a child, the interpreter must be closer to the child so he avoids being perceived as a person of particular power and ensures that the asylum seeker feels comfortable with him.

The interviewer

The appearance of the interviewer is very crucial: if it is very formal it might be frightening for the asylum seeker and make him feel uneasy and unwilling to communicate. The clothing of the interviewer ought to show that he respects the asylum seeker and in particular his cultural origin so as to be well received.

The interviewer must not act nervously or slouch on their seat.

The interviewer must not look outside the window.

The interviewer must not make gestures or point (by moving his head or turning their gaze to the ceiling) in a way that suggests disagreement with the interviewee’s narration or disbelief of the truthfulness of his story.

The interviewer should encourage the asylum seeker even if there is an expression of hesitation or silence. The interviewer can nod affirmatively, saying ‘…and after?’, ‘I understand…’ or repeat keywords from the asylum seekers previous answer.

The interviewer must avoid examining any document, it is advised that he waits until his conversation with the asylum seeker ends. The questions are directly addressed to the asylum seeker and not ‘through’ the interpreter.

For example: NO! (speaking to the interpreter) ‘Ask what happened after the bomb explosion’. YES! (directly to the asylum seeker) ‘What happened after the bomb explosion?’.

The tone of the voice must not be threatening but always encouraging and able to persuade the asylum seeker to respond with honesty and trust to the questions he is being asked by the interviewer.

The interpreter

In many occasions the interview is conducted with the contribution of an interpreter, a fact that might add an additional barrier to the communication with the asylum seeker. The interpreter should be aware of the code of conduct of the interview.

An interpreter must not indulge in general conversation with the claimant before (other than to establish both speak the same language and/or dialect), during or after an assignment.

The interpreter must not attempt to improve the asylum seeker’s speech in his effort to present the asylum seeker to the interviewer as an image of a person characterised by coherency, trustworthiness or education. It is important that the interpreter knows that the asylum seeker and the interviewer are entitled to ask explanatory questions, when deemed necessary.

It is of critical importance that the relation of the interpreter to the asylum seeker does not influence the willingness and capacity for communication. This is important not only for securing the objectivity/neutrality of the interview process, but also to avoid any pressure from the asylum seeker towards the interpreter.

The interpreter must spell out any foreign name or place said by the interviewee.

They must use direct speech when interpreting; for example, the interpreter must say: ‘I attended a demonstration ......’, and should not say: ‘he said he attended ......’.

*The above extracts have been translated by Danae Io from the following document: ‘Interviewing Applicants For Refugee Status’, UNHCR, 2014. Available from refworld.org.

III

Last summer, we spent three months in Athens attempting to understand how interviews are situated within the process of seeking asylum. We became interested in the ways in which the interview scenario is an example of how certain aspects of the asylum application confine human experience within bureaucracy. The interview is made up of a triad – interviewer, interviewee and interpreter – and specific and distinct relationships are produced between the vertices of this triangle, linking each participant along divergent planes. Through the interpreter, the asylum seeker is linguistically connected to the interviewer, who holds a position of power and could be said to occupy the top point. Written guidelines describe and bind how each must ‘act’ within this scenario. We spent time investigating these guidelines, discovering granular details ranging from body language to tone of voice to ways of directing and inflecting questions. We began to recognise a performativity within these observations: interviewers read prescribed scripts which guide the asylum seeker’s behaviour; interviewees deliver their much rehearsed narrative; interpreters embody these two voices, relaying information between one and the other.

During the interview, the interpreter is spatially placed closer to the interviewer, rather than the asylum seeker. This pushes against the neutrality and objectivity that are supposedly well-regarded values within the interview: the spatial arrangement both displays and produces power relations. Through staging this interview, we observed the presence of a multiplicity of further power relations. There exists an interviewer– interviewee host–guest dynamic: one hosts the other as they enter into the former’s receiving country. However, this relationship does not solely exist within the context of the interview. While in Athens, we started to notice a language of hospitality present in the very fabric of architectures associated with the ‘refugee journey’. For example, the Amygdaleza Pre-Removal Detention Centre in the northwest of Athens displays the sign: ‘The construction of the hospitality of illegal immigrants centre has been co-financed by the European Return Fund’. This sort of language both creates, and is constituted by, distinct power relations. We found potentially productive parallels between this and Jacques Derrida’s short polemic Of Hospitality. He claims that the asylum seeker is in a position where they must ‘ask for hospitality in a language which, by definition is not [their] own, the one imposed on him by the master of the house, the host, the king, the lord, the authorities, the nation, the State, the father’.1 Similarly to the interview, this process imposes on the asylum claimant a translation into their own language. Derrida states this is the ‘first act of violence’2 upon entering a host country, questioning, ‘Does hospitality consist in interrogating the new arrival?’3